inutile parlarne sai,

non capiresti mai

essay by João Paupério e Maria Rebelo (atelier local)

The future was in the present, where the past ought to be

The San Siro stadium is a monument. We do not say this lightly: either due to the imposing dimension of its towers, the majesty of its red crown of trusses, or for its long history of successes. From an objective point of view, the San Siro stadium is one of the largest in Europe. Nonetheless, if we claim it is a monument, it is above all because it is already part of our collective memory. Not just for those who enjoy football in particular, but for those who appreciate the best that can be found in sports.

As an idea, San Siro is able to cross borders: not just those of Italy, but those of football itself. The San Siro is not only in Milan. The San Siro is also in Valongo, a small town on the outskirts of Porto where we live and work, and where fans of the local roller hockey club decided to call their small municipal pavilion San Siro, to to describe the atmosphere felt inside. A place where even a small team with little resources is capable of rising up and beat the best teams. For them, as for many others, San Siro is not merely a building. It is also, first and foremost, a state of mind.

The San Siro is a monument because it is a collective work, built throughout the long duration of time. As a work of art, San Siro is one of those buildings that perfectly illustrate the principle to which Godard was pointing to when he wrote: CLASSIQUE=MODERNE. As well as what Lawrence Weiner may have meant when he stated that all “this crap rubbish about generations makes no sense whatsoever. All people walking on the earth at the same time belong to the same generation.” The resilience of the San Siro, its ability to grow, transform and reinvent itself throughout history, responding to the demands of hundreds of thousands of fans from different generations, seems to unveil something similar about architecture. At the end of the day, classic and modern are made of the same and for that reason it makes as little sense to freeze heritage in time as to declare it hopelessly obsolete.

San Siro is a monument because it illustrates in and of itself a considerable part of history, both in terms of football as in terms of architecture proper. At the San Siro, several “generations” and several “lessons” of architecture coexist in a single space-time. From the San Siro, our imagination may leap either to the most beautiful achievements of the Soviet constructivists as to the British neo-brutalists, who were emerging in force at the same time as its ramps were being erected. From San Siro one may also learn the meaning of the vitruvian triad, which in varying proportions has served as a foundation to the history of Western architecture: firmitas, utilitas and venustas. This is, of course, because the San Siro remains firm, remains useful and remains beautiful. Otherwise, it would not remain a symbol of such magnitude.

If as an architectural device the purpose of a stadium is to allow a football match to take place in the best conditions, for the best team to win, and for the fans to intensely enjoy those victories, no one is allowed to claim that the San Siro stadium is now obsolete. Both Inter and AC Milan remain two of the most competitive teams in Italy and every football fan still wishes that one day they could watch a match in the cauldron of San Siro. The stadium became a monument because it is alive, because some of the best football matches are still played there and no-one would guess that its centenary will be celebrated any time soon.

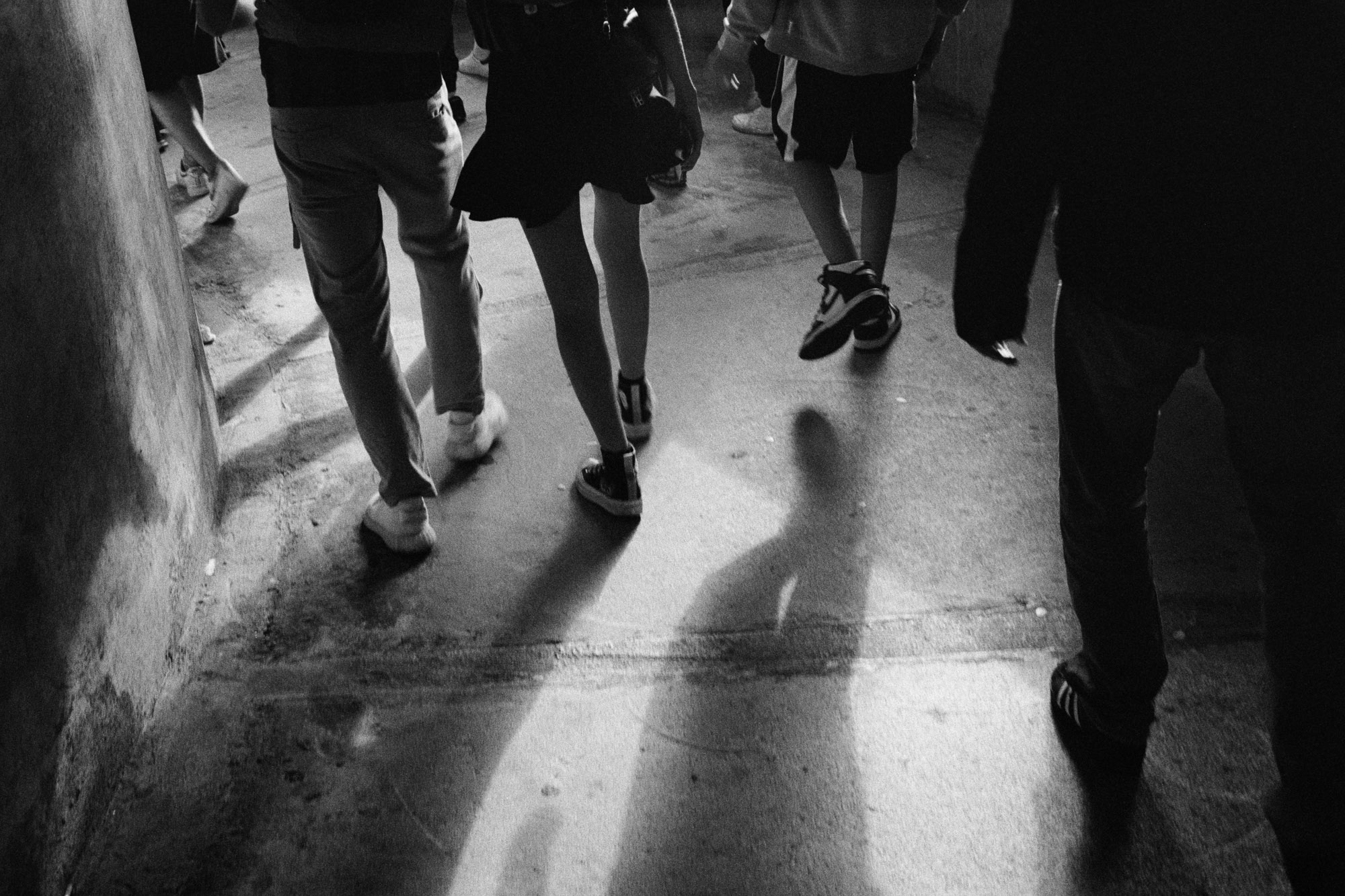

Its Solomonic columns, without a base but with expressive shafts and capitals, evoke not only classicist but also modern principles, which have found in flow management a fundamental problem for an architecture of there New Spirit. The agility with which spectators are led from the city to their seats, an essential aspect for the smooth running of a stadium, turns at the San Siro into a matter of composition rather than mere efficiency. Ramps become elevations, crowned by a frieze that happens to function as a grandstand. This path to the interior is extended into a veritable architectural promenade, intensifying a ritualistic experience that is indispensable for any supporter travelling into a stadium: the feeling of anticipation and expectation that grows with the proximity of the starting whistle, which have been so well illustrated by Yuri Ancarani's movement-images. At San Siro, performance becomes perfomativity, proving that reason has never really excluded ornament from its sight; or in other words, that a stadium can be as much a silo as it is a temple.

In addition to its architecture, San Siro was also a symbol of something rare in the world of football: the fraternity and co-operation which is possible between two eternal rivals. And yet, like practically everything else in this world, the best of sports has also been taken over by the icy waters of selfish calculation and shady financial interests. More than a sport, football has become an important sector of financial investment in recent years. In 2019, both teams presented a project to build a new joint stadium, agreeing that the San Siro was obsolete according to contemporary standards of efficiency and performance, as well as claiming that its refurbishment would have too high an impact in terms of immediate return. A solution which involved demolishing the old San Siro, under the absurd pretence that it would be replaced by a “greener” and “more sustainable” stadium, with nearly “zero impact”. As if the demolition of a historic stadium, with all the energy and spoils it entails, would not in itself be an environmental and emotional outrage: a senseless crime of which the photographs now taken by Luca Bosco and Francisco Ascensão now appear as new clues.

In the meantime, San Siro's protected heritage status prevented it from being demolished. However, instead of abandoning their absurd project, Inter and AC Milan preferred to it a step forward, deciding instead to build not only one, but two new stadiums, putting an end to decades of mutualism. As Pier Paolo

Tamburelli, who was probably the most vocal of Italian architects against the abandonment of the San Siro, has already written, “a great building like the San Siro can always be adapted, as long as you can also (marginally) adapt the standards by which it is measured, as long as you accept that between the stands and the restaurant there may be nineteen steps instead of seventeen”. In order for this to possibly happen, though, the problem would have to be truly one of architecture and not one of financial interests, as it seems increasingly clear is the case. In other words, it would have to be a real problem for architecture as a spatial device, and not as an instrument for fine-tuning the engines of gentrification and property speculation.

San Siro is undoubtedly the most ecological stadium, because it already exists. San Siro is the most economical stadium, because it already exists. San Siro is the most beautiful stadium, because it already exists and the patina of countless victories is inscribed on its walls. For all these reasons, the San Siro is a monument. For all these reasons, keeping it alive would be a gesture of resistance against the destruction of football (like so many other commons of humanity) by obscure interests that are not, in fact, those of the people who watch football for the beauty of the sport. Everything else they might claim is just a series of greenwashing manoeuvres of the same calibre as those that would have us believe that lithium batteries are going to save the world.

As we approach the end of this text, we realise that we may no longer have time to attend a match at the San Siro. It is probably too late and that saddens us. The future of the San Siro was in the present, where its past ought to be. Now, it seems, the stadium itself will remain a monument: but haunted by everything else, it will henceforth become, above all, the symbol of an irremediable defeat.

The future was in the present, where the past ought to be

The San Siro stadium is a monument. We do not say this lightly: either due to the imposing dimension of its towers, the majesty of its red crown of trusses, or for its long history of successes. From an objective point of view, the San Siro stadium is one of the largest in Europe. Nonetheless, if we claim it is a monument, it is above all because it is already part of our collective memory. Not just for those who enjoy football in particular, but for those who appreciate the best that can be found in sports.

As an idea, San Siro is able to cross borders: not just those of Italy, but those of football itself. The San Siro is not only in Milan. The San Siro is also in Valongo, a small town on the outskirts of Porto where we live and work, and where fans of the local roller hockey club decided to call their small municipal pavilion San Siro, to to describe the atmosphere felt inside. A place where even a small team with little resources is capable of rising up and beat the best teams. For them, as for many others, San Siro is not merely a building. It is also, first and foremost, a state of mind.

The San Siro is a monument because it is a collective work, built throughout the long duration of time. As a work of art, San Siro is one of those buildings that perfectly illustrate the principle to which Godard was pointing to when he wrote: CLASSIQUE=MODERNE. As well as what Lawrence Weiner may have meant when he stated that all “this crap rubbish about generations makes no sense whatsoever. All people walking on the earth at the same time belong to the same generation.” The resilience of the San Siro, its ability to grow, transform and reinvent itself throughout history, responding to the demands of hundreds of thousands of fans from different generations, seems to unveil something similar about architecture. At the end of the day, classic and modern are made of the same and for that reason it makes as little sense to freeze heritage in time as to declare it hopelessly obsolete.

San Siro is a monument because it illustrates in and of itself a considerable part of history, both in terms of football as in terms of architecture proper. At the San Siro, several “generations” and several “lessons” of architecture coexist in a single space-time. From the San Siro, our imagination may leap either to the most beautiful achievements of the Soviet constructivists as to the British neo-brutalists, who were emerging in force at the same time as its ramps were being erected. From San Siro one may also learn the meaning of the vitruvian triad, which in varying proportions has served as a foundation to the history of Western architecture: firmitas, utilitas and venustas. This is, of course, because the San Siro remains firm, remains useful and remains beautiful. Otherwise, it would not remain a symbol of such magnitude.

If as an architectural device the purpose of a stadium is to allow a football match to take place in the best conditions, for the best team to win, and for the fans to intensely enjoy those victories, no one is allowed to claim that the San Siro stadium is now obsolete. Both Inter and AC Milan remain two of the most competitive teams in Italy and every football fan still wishes that one day they could watch a match in the cauldron of San Siro. The stadium became a monument because it is alive, because some of the best football matches are still played there and no-one would guess that its centenary will be celebrated any time soon.

Its Solomonic columns, without a base but with expressive shafts and capitals, evoke not only classicist but also modern principles, which have found in flow management a fundamental problem for an architecture of there New Spirit. The agility with which spectators are led from the city to their seats, an essential aspect for the smooth running of a stadium, turns at the San Siro into a matter of composition rather than mere efficiency. Ramps become elevations, crowned by a frieze that happens to function as a grandstand. This path to the interior is extended into a veritable architectural promenade, intensifying a ritualistic experience that is indispensable for any supporter travelling into a stadium: the feeling of anticipation and expectation that grows with the proximity of the starting whistle, which have been so well illustrated by Yuri Ancarani's movement-images. At San Siro, performance becomes perfomativity, proving that reason has never really excluded ornament from its sight; or in other words, that a stadium can be as much a silo as it is a temple.

In addition to its architecture, San Siro was also a symbol of something rare in the world of football: the fraternity and co-operation which is possible between two eternal rivals. And yet, like practically everything else in this world, the best of sports has also been taken over by the icy waters of selfish calculation and shady financial interests. More than a sport, football has become an important sector of financial investment in recent years. In 2019, both teams presented a project to build a new joint stadium, agreeing that the San Siro was obsolete according to contemporary standards of efficiency and performance, as well as claiming that its refurbishment would have too high an impact in terms of immediate return. A solution which involved demolishing the old San Siro, under the absurd pretence that it would be replaced by a “greener” and “more sustainable” stadium, with nearly “zero impact”. As if the demolition of a historic stadium, with all the energy and spoils it entails, would not in itself be an environmental and emotional outrage: a senseless crime of which the photographs now taken by Luca Bosco and Francisco Ascensão now appear as new clues.

In the meantime, San Siro's protected heritage status prevented it from being demolished. However, instead of abandoning their absurd project, Inter and AC Milan preferred to it a step forward, deciding instead to build not only one, but two new stadiums, putting an end to decades of mutualism. As Pier Paolo

Tamburelli, who was probably the most vocal of Italian architects against the abandonment of the San Siro, has already written, “a great building like the San Siro can always be adapted, as long as you can also (marginally) adapt the standards by which it is measured, as long as you accept that between the stands and the restaurant there may be nineteen steps instead of seventeen”. In order for this to possibly happen, though, the problem would have to be truly one of architecture and not one of financial interests, as it seems increasingly clear is the case. In other words, it would have to be a real problem for architecture as a spatial device, and not as an instrument for fine-tuning the engines of gentrification and property speculation.

San Siro is undoubtedly the most ecological stadium, because it already exists. San Siro is the most economical stadium, because it already exists. San Siro is the most beautiful stadium, because it already exists and the patina of countless victories is inscribed on its walls. For all these reasons, the San Siro is a monument. For all these reasons, keeping it alive would be a gesture of resistance against the destruction of football (like so many other commons of humanity) by obscure interests that are not, in fact, those of the people who watch football for the beauty of the sport. Everything else they might claim is just a series of greenwashing manoeuvres of the same calibre as those that would have us believe that lithium batteries are going to save the world.

As we approach the end of this text, we realise that we may no longer have time to attend a match at the San Siro. It is probably too late and that saddens us. The future of the San Siro was in the present, where its past ought to be. Now, it seems, the stadium itself will remain a monument: but haunted by everything else, it will henceforth become, above all, the symbol of an irremediable defeat.